The Destruction of Mecca

By ZIAUDDIN SARDAR

SEPT. 30, 2014 The New York

Times

WHEN Malcolm X visited Mecca in 1964, he was enchanted. He

found the city “as ancient as time itself,” and wrote that the partly

constructed extension to the Sacred Mosque “will surpass the architectural

beauty of India’s Taj Mahal.”

Fifty years on, no one could possibly describe Mecca as

ancient, or associate beauty with Islam’s holiest city. Pilgrims performing the

hajj this week will search in vain for Mecca’s history.

The dominant architectural site in the city is not the

Sacred Mosque, where the Kaaba, the symbolic focus of Muslims everywhere, is.

It is the obnoxious Makkah Royal Clock Tower hotel, which, at 1,972 feet, is

among the world’s tallest buildings. It is part of a mammoth development of

skyscrapers that includes luxury shopping malls and hotels catering to the

superrich. The skyline is no longer dominated by the rugged outline of

encircling peaks. Ancient mountains have been flattened. The city is now

surrounded by the brutalism of rectangular steel and concrete structures — an

amalgam of Disneyland and Las Vegas.

The “guardians” of the Holy City, the rulers of Saudi Arabia

and the clerics, have a deep hatred of history. They want everything to look

brand-new. Meanwhile, the sites are expanding to accommodate the rising number

of pilgrims, up to almost three million today from 200,000 in the 1960s.

The initial phase of Mecca’s destruction began in the

mid-1970s, and I was there to witness it. Innumerable ancient buildings,

including the Bilal mosque, dating from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, were

bulldozed. The old Ottoman houses, with their elegant mashrabiyas — latticework

windows — and elaborately carved doors, were replaced with hideous modern ones.

Within a few years, Mecca was transformed into a “modern” city with large

multilane roads, spaghetti junctions, gaudy hotels and shopping malls.

The few remaining buildings and sites of religious and

cultural significance were erased more recently. The Makkah Royal Clock Tower,

completed in 2012, was built on the graves of an estimated 400 sites of

cultural and historical significance, including the city’s few remaining

millennium-old buildings. Bulldozers arrived in the middle of the night,

displacing families that had lived there for centuries. The complex stands on

top of Ajyad Fortress, built around 1780, to protect Mecca from bandits and

invaders. The house of Khadijah, the first wife of the Prophet Muhammad, has

been turned into a block of toilets. The Makkah Hilton is built over the house

of Abu Bakr, the closest companion of the prophet and the first caliph.

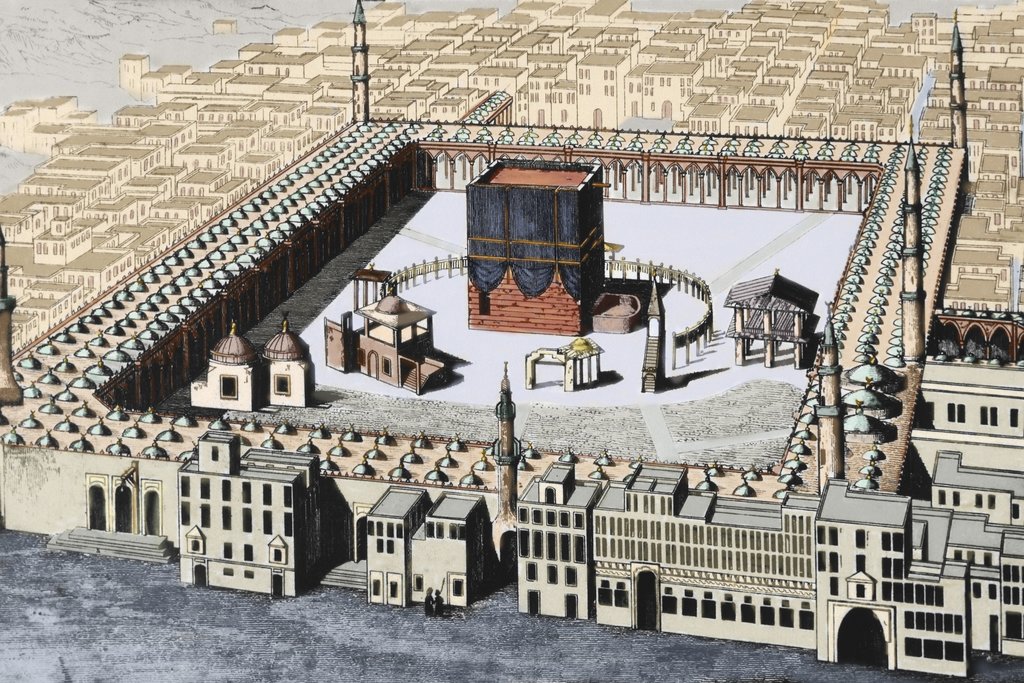

Mecca Over the Years

Apart from the Kaaba itself, only the inner core of the

Sacred Mosque retains a fragment of history. It consists of intricately carved

marble columns, adorned with calligraphy of the names of the prophet’s companions.

Built by a succession of Ottoman sultans, the columns date from the early 16th

century. And yet plans are afoot to demolish them, along with the whole of the

interior of the Sacred Mosque, and to replace it with an ultramodern

doughnut-shaped building.

The only other building of religious significance in the

city is the house where the Prophet Muhammad lived. During most of the Saudi

era it was used first as a cattle market, then turned into a library, which is

not open to the people. But even this is too much for the radical Saudi clerics

who have repeatedly called for its demolition. The clerics fear that, once

inside, pilgrims would pray to the prophet, rather than to God — an

unpardonable sin. It is only a matter of time before it is razed and turned,

probably, into a parking lot.

The cultural devastation of Mecca has radically transformed

the city. Unlike Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo, Mecca was never a great

intellectual and cultural center of Islam. But it was always a pluralistic city

where debate among different Muslim sects and schools of thought was not

unusual. Now it has been reduced to a monolithic religious entity where only

one, ahistoric, literal interpretation of Islam is permitted, and where all

other sects, outside of the Salafist brand of Saudi Islam, are regarded as

false. Indeed, zealots frequently threaten pilgrims of different sects. Last

year, a group of Shiite pilgrims from Michigan were attacked with knives by

extremists, and in August, a coalition of American Muslim groups wrote to the

State Department asking for protection during this year’s hajj.

The erasure of Meccan history has had a tremendous impact on

the hajj itself. The word “hajj” means effort. It is through the effort of

traveling to Mecca, walking from one ritual site to another, finding and

engaging with people from different cultures and sects, and soaking in the

history of Islam that the pilgrims acquired knowledge as well as spiritual

fulfillment. Today, hajj is a packaged tour, where you move, tied to your group,

from hotel to hotel, and seldom encounter people of different cultures and

ethnicities. Drained of history and religious and cultural plurality, hajj is

no longer a transforming, once-in-a-lifetime spiritual experience. It has been

reduced to a mundane exercise in rituals and shopping.

Mecca is a microcosm of the Muslim world. What happens to

and in the city has a profound effect on Muslims everywhere. The spiritual

heart of Islam is an ultramodern, monolithic enclave, where difference is not

tolerated, history has no meaning, and consumerism is paramount. It is hardly

surprising then that literalism, and the murderous interpretations of Islam

associated with it, have become so dominant in Muslim lands.

Ziauddin Sardar is the editor of the quarterly Critical

Muslim and the author of “Mecca: The Sacred City.”